BUFFALO, NY -Ask managers what they think is the most effective employee motivator and the likely responses will include “recognition,” “incentives” or “pay raises.”

These answers are wrong.

“Of all the events at the office that have the power to excite and engage employees, the single most important is making progress in meaningful work,” says Teresa Amabile ’72, HON ’97, PhD.

Amabile is the Edsel Bryant Ford Professor of Business Administration and a director of research at Harvard Business School. She is also a leading authority on the business of creativity.

“It’s a myth that artists are the only creative people, since all human progress depends on creativity for the production of something new and useful,” says Amabile.

Creative thinking is credited with the rise of such contemporary behemoths as Facebook and Google. It’s also enabled the continued success of consumer goliaths Procter & Gamble and General Electric.

“Creativity in business involves coming up with ideas for new products, new services or new ways of doing business, which are sustainable, can generate profit or meet the goals of the organization,” Amabile adds.

Creative Spark

Amabile has made the study of creativity her life’s work.

She originally focused on how intrinsic motivation influences individual creativity. While pursuing her PhD in psychology at Stanford University, she discovered that “people are more creative when they are doing something interesting, challenging and personally satisfying to them.” Amabile later expanded her research to include team creativity and organizational innovation.

Her most recent research examines how events in the workplace influence creativity, productivity and commitment. Amabile collaborated on the study and the book that followed (The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement and Creativity at Work) with Steven Kramer, PhD, a developmental psychologist and Amabile’s husband of 23 years.

“One of the most frequent questions we get is not about the content of the book or the research behind it,” laughs Amabile. “Rather it’s ‘You guys wrote a book together and are still married?’”

Amabile admits to the couple’s different work styles. But these differences complemented one another and by working together, the couple accomplished more than either could have alone.

“We set out to do this research together because we wanted to make a positive difference in the work lives of as many people and organizations as possible,” she says.

Dear Diary

Amabile and Kramer’s in-depth, multi-year study asked 238 professionals, from various industries, to keep daily electronic diaries about their inner work lives. (These are the perceptions, emotions and motivations that people experience as they react to and make sense of the events in their workdays.) An analysis of the nearly 12,000 diary entries looked at trends and patterns in stories, and revealed a surprising discovery, which Amabile refers to as the progress principle.

“On days when employees sensed they made headway in meaningful work, their emotions were more positive, their drive to perform peaked, and they had more favorable perceptions of their work environment,” says Amabile, who defines “meaningful work” as any work that gives employees a sense of purpose. “In turn, such positive inner work life makes employees more likely to be productive and creative.”

Even minor victories yielded major returns.

“People often felt ecstatic,” says Amabile, when they accomplished simple tasks, such as tweaking an algorithm to make a new process or fixing a bug in a software problem. These small but meaningful wins boosted people’s motivation and emotions more than any extrinsic motivator, such as rewards or recognition.

“We were stunned,” adds Amabile, “by the depth and emotionality of how important people’s work is to them personally. Most of the people we studied were not merely working for a paycheck. They care deeply about their work, their colleagues and the organizations of which they are a part.”

Creativity and the Bottom Line

Small, meaningful wins aren’t just big deals for employees. They can be critical to a corporation’s bottom line. Consider this: An alarming 70 percent of today’s workers feel unengaged in or unenthusiastic about their work, according to Gallup’s “State of the American Workplace” report (2010-2012). The price tag for this equates to about $450 billion in lost productivity, each year.

“If you’re a manager of people, these findings make it clear where you need to focus your efforts,” says Michael Cardus, president of Create-Learning Team Building & Leadership. An executive trainer and leadership coach, Cardus educates professionals on how to apply the progress principle. “Most managers don’t fully understand the power they have to help employees succeed in their work.”

That power lies in seven simple catalysts that can positively impact people’s inner work lives and the work, itself. A few of these catalysts are outlined below:

Supporting the Work

In chemistry, a catalyst is a substance that initiates or accelerates a chemical reaction. When discussing her research, Amabile (whose undergraduate degree is in chemistry) uses the term to describe the actions managers can take to give people the best chance of achieving meaningful progress.

Setting clear goals is perhaps the paramount catalyst.

“People feel energized about their work when they know where it’s headed and why it matters,” explains Amabile. Sounds like Management 101 but ambiguity is common place from Cardus’ perspective.

“Managers like to talk in big, abstract ways that really have no meaning for the people in the trenches,” he says. “This leaves employees feeling confused about what is expected of them, where to focus their efforts or how their work brings value to the organization.”

Instead, Amabile suggests breaking down big, lofty goals into specific, measureable, attainable and time-bound parts. “This way, you’re setting up a series of tangible small wins that facilitate consistent progress,” she says.

As much as employees need specific goals, they also need the freedom to figure out how to achieve those goals. Autonomy lets individuals determine the “means” to the “end” in a way that capitalizes on their expertise and creativity. It’s empowering, self-starting and another catalyst to meaningful progress.

Autonomy, however, is not the same as isolation.

“The last thing we want is to have a bunch of people working behind closed doors,” says Diego Rodriguez, a partner at the global design firm IDEO, which Amabile is currently studying. IDEO is one of the most influential innovation firms in the world. The company developed the first computer mouse for Apple, a better Pringle for Procter & Gamble, and the stand-up toothpaste tube. All these innovations – and more- were born out of a corporate culture that fosters the free flow of ideas.

“People here have access to everyone around them,” adds Rodriguez. “It’s this type of environment that enables us to build upon the ideas of others and ultimately get to a place that you just can’t get to with one mind.”

Still, no matter how capable people are or how well they perform their jobs, setbacks are inevitable. Sometimes, setbacks occur in the natural course of experimentation. Other times, they happen because of organizational hindrances. Whatever the reason, managers beware. Setbacks, says Amabile, are “the dark side” of the progress principle.

“Of all the events that can destroy engagement and undermine creativity and productivity, having setbacks is number one,” says Amabile. “Even worse, the negative effects of setbacks are two-to-three times greater than the positive effects of progress.”

Managers can neutralize the negative effects of setbacks and get progress back on track by removing obstacles, and working with employees to learn from problems.

“We have a saying here that you learn more when things start breaking,” says Rodriguez. “That’s when new discoveries are made, better business models are developed for clients or we figure out how to tell their stories in more effective ways.”

When people make discoveries or figure things out, they find joy, engagement and creativity at work. And when they feel great about the work they do, they want to do more great work.

The Progress Loop

“One really feeds the other,” says Amabile, who refers to this cycle as the progress loop. It’s the secret weapon of most high performance companies but its benefits are most definitely universal.

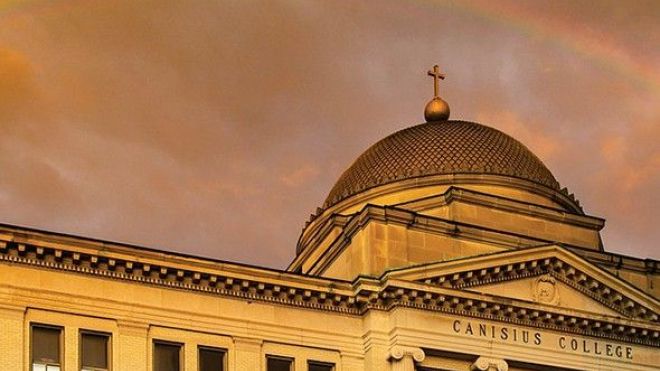

“Everyone can take something from the progress principle, no matter their profession,” says Kara Schwabel, PhD. As director of differentiated instruction at Canisius, Schwabel teaches education students how they can apply elements of the progress principle in their future classrooms. “Ultimately, it’s about human beings – adults and children. It’s about figuring out their potentials and how to harness their individual gifts so that they may each move forward with what truly motivates and inspires them because at the end of the day, everyone wants to succeed and contribute to something bigger.”

The result is a win-win and proof that creativity, productivity and commitment are not just measured in quarterly reports but rather in the meaningful progress made by everyday people, every day.

Teresa Amabile's "Daily Progress Checklist" provides managers with a practical framework for implementing the progress principle. Check it out by clicking here.